First off, I hope everyone has enjoyed a lovely and peaceful holiday season. Best wishes to all of you for 2012.

Since I reported on my findings at the La Reunion site in Dallas County last month, I learned a little more about the scant remains of that old house on the original colony site. Turns out that the homestead appears to be that of La Reunion colonist Leon DeLord, who built the house with his son Alphonse. The only thing is, according to Emanuel Santerre, last survivor of the French colony, the DeLord house - remnants of which I photographed and posted on the blog - was built after the La Reunion colony officially dissolved.

The DeLord site can be found somewhere along Westmoreland Road on the old colony site. Thousands of commuters probably pass by it every day without realizing the historical significance of the old homestead. The Episcopal Diocese of Dallas apparently owned the plot for some time, but now it seems unclear as to whom, if anyone, is responsible for the site. And it may not be part of the actual La Reunion colony itself like the cemetery on nearby Fish Trap Road, but it may be as close as anyone gets.

Then again, I've heard rumors of other possible ruins at the La Reunion site, but I'll have to file that under "To Be Continued."

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Sunday, December 4, 2011

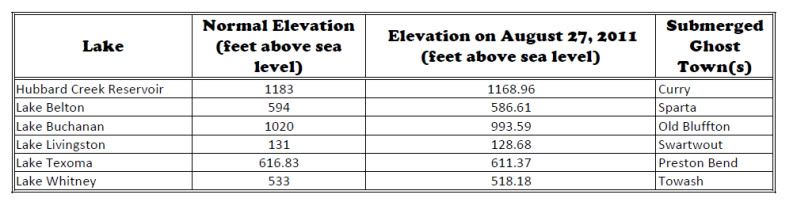

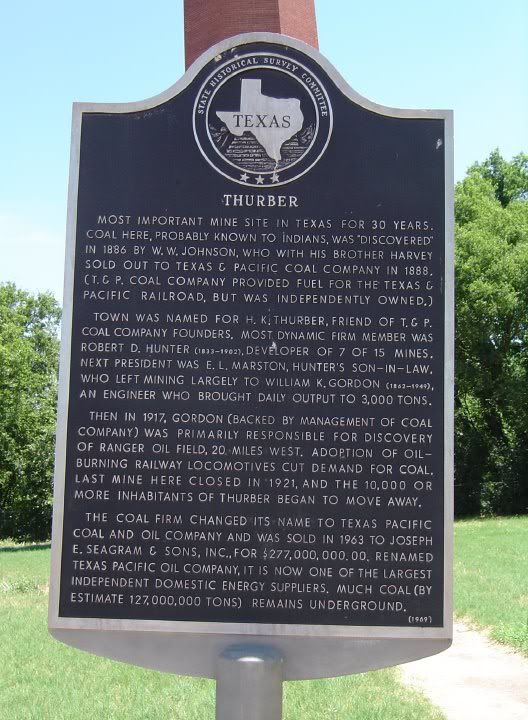

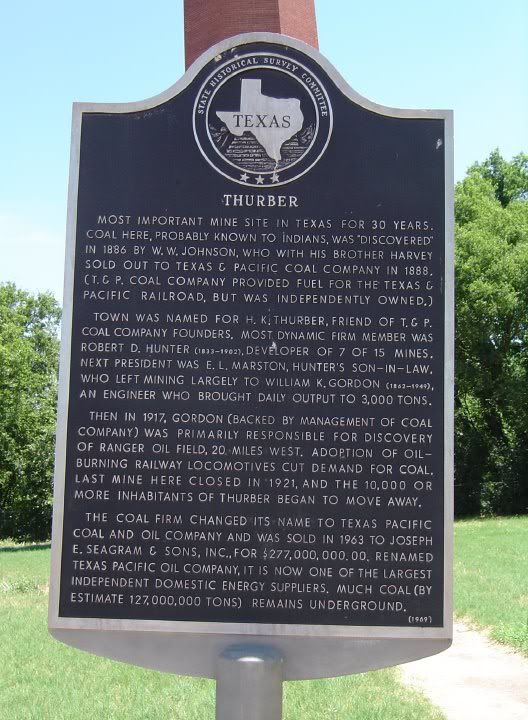

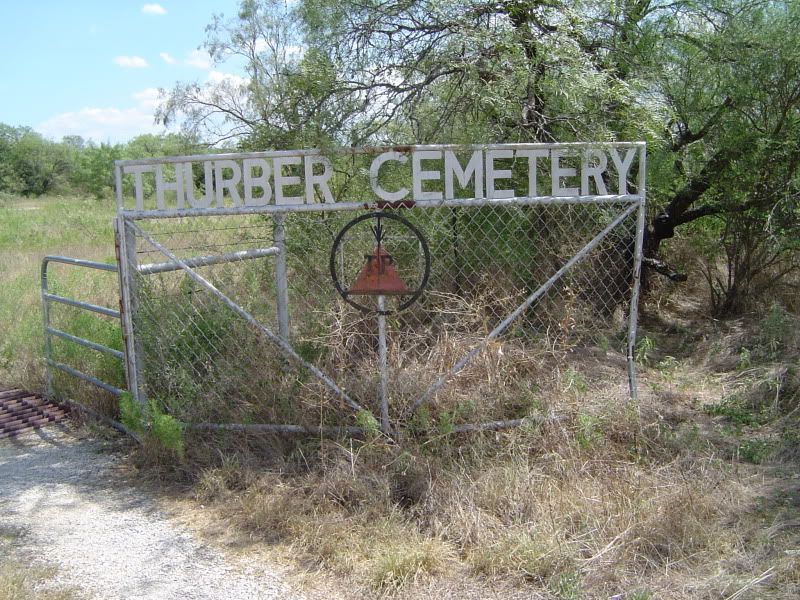

Museum at Thurber receives $5,000,000 grant

This news is admittedly a bit old by now, but definitely worth sharing in light of my previous coverage of the Erath County ghost town of Thurber. Last month, Tarleton State University announced a gift of $6 million from Mrs. W.K. Gordon, Jr. and the W.K. Gordon, Jr. Foundation. $5 million of the gift will be used to fund the W.K. Gordon Center for the Industrial History of Texas in Thurber, named for Mrs. Gordon's father-in-law - one of the most prominent men in Thurber's history.

The W.K. Gordon Center really is an interesting museum and a fitting tribute to the legacy of Thurber. Please include it on your itinerary whenever you're able to visit this ghost town.

The W.K. Gordon Center really is an interesting museum and a fitting tribute to the legacy of Thurber. Please include it on your itinerary whenever you're able to visit this ghost town.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

18 months - a personal milestone

Yesterday, I paid a visit to the scant remains of the Burning Bush settlement on the border of Smith County and Cherokee County. Not much left - just a historical marker and the crumbling remains of an old Burning Bush barn, both now on private property and completely surrounded by the town of Bullard. This much, however, is just enough.

Since May 2010, I have paid a visit to at least one Texas ghost town every month. I've only shared a few of my exploits so far on this blog, but I hope you've enjoyed what I've presented so far. As I mentioned earlier, I see these trips as a form of personal therapy; besides, I've never really put together a formal "bucket list," but visiting ghost towns would clearly be on such a list. I'll keep doing this as long my car, my finances, and my health allow me.

Since May 2010, I have paid a visit to at least one Texas ghost town every month. I've only shared a few of my exploits so far on this blog, but I hope you've enjoyed what I've presented so far. As I mentioned earlier, I see these trips as a form of personal therapy; besides, I've never really put together a formal "bucket list," but visiting ghost towns would clearly be on such a list. I'll keep doing this as long my car, my finances, and my health allow me.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

La Reunion (Dallas County) - August 2010/October 2010 photos

In Dallas County, the big'uns ate the small'uns - it was the logical progression of municipal growth. The towns of Embree and Duck Creek joined forces in 1891 and transformed into the single city of Garland, which still endures today as, among other things, the birthplace of yours truly. Most towns, however, wound up being devoured by a larger and more successful neighbor. Irving gobbled up the communities of Kit and Sowers, leaving only a cemetery or two as evidence that these towns ever existed. Richardson encircled the semi-rural village of Buckingham and finally annexed it in 1996. As for Dallas, over the past 150 years, it devoured numerous towns and settlements throughout Dallas County, including Jimtown, Scyene, Lisbon, Vickery, Fisher, Letot, Oak Cliff, and what remained of a little French colony known as La Reunion. Small pond, meet big fish.

All the other towns have pretty much assimilated into Dallas without leaving any trace of their former selves, and that makes the story of La Reunion all the more fascinating to me. Settled in 1854 and officially founded the next year to serve as a communal society operating on the socio-economic principles espoused by French philosopher Francois Marie Charles Fourier, the town sat on the Trinity River, three miles west of what used to be the village of Dallas. 200 immigrants from France, Belgium, and Switzerland got the project started, and while some of the colonists moved on, there were enough new arrivals to keep La Reunion operating for approximately 18 months, with the population peaking at 350 in late 1856.

La Reunion had everything working against it. The limestone soil proved to be a constant frustration for agriculturists. The colony was plagued with ineffective leadership and disorganization, not to mention financial insolvency. On January 28, 1857, La Reunion was officially dissolved. A few holdouts purchased land on the La Reunion tract and made the site their permanent home, but most colonists either returned to Europe or resettled in Dallas, San Antonio, or New Orleans.

When Dallas expanded westward and swallowed what was left of La Reunion, the townsite was excavated for lime used in the manufacture of concrete, which was sorely needed by the growing city; in fact, the site of La Reunion was incorporated as the town of Cement City for a few decades. Reunion Tower and the now-demolished Reunion Arena were named after the old colony, but at first glance, there seems to be nothing left of La Reunion; instead, there are houses, schools, buinesses, and a golf course in Stevens Park. Walk through the golf course, and you'll see a stone erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1924.

Granite DAR memorial at the Stevens Park golf course, marking the La Reunion site

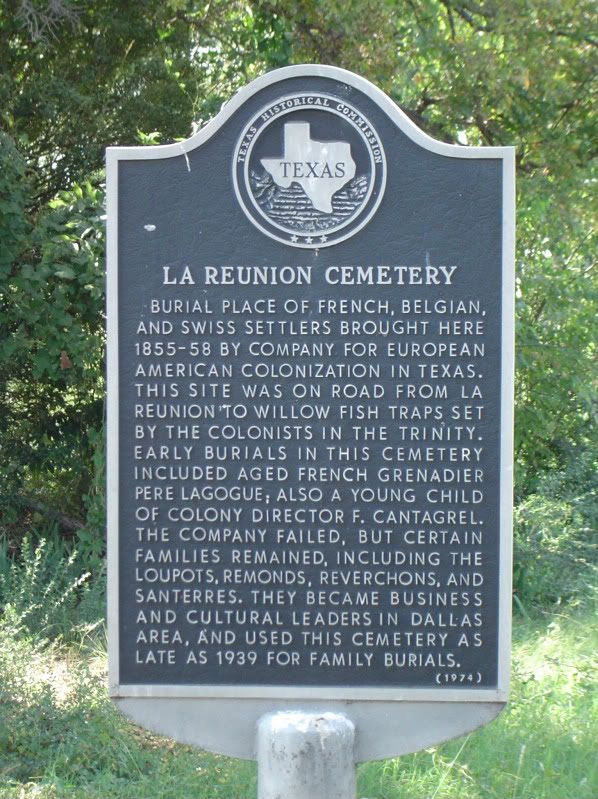

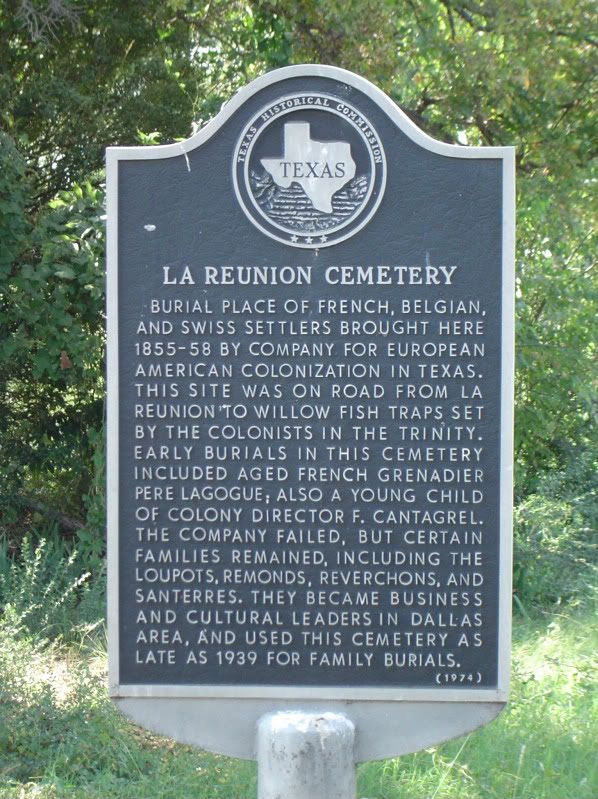

The DAR memorial is a lovely tribute, but obviously not part of the original colony. For that, travel over to L.G. Pinkston High School at 3345 Fish Trap Road in Dallas and face northwest from the school. You'll be looking at a housing development, and right next to it there is a semi-neglected cemetery that was once known as Fish Trap Cemetery, but a historical marker within the chainlink fence surrounding the cemetery proclaims this the burial site for some of the La Reunion colonists:

Historical marker for La Reunion Cemetery on Fish Trap Road in Dallas

According to a Dallas Morning News article on La Reunion Cemetery, there has been considerable difficulty finding which agency is responsible for the cemetery's upkeep. Some determined volunteers are doing what they can to tend to the cemetery, and once in a while, some enterprising ghost town chaser finds his way into the cemetery as well. Here are some of the graves at the site:

Tombstone for botanist Julien Reverchon and his wife Marie, both La Reunion colonists; Reverchon Park in Dallas is named in Julien's honor

Broken grave marker for Michel Reverchon, son of Julien and Marie Reverchon

Francois Santerre, one of the most prominent La Reunion colonists, is buried here with his wife, Marie

Not everyone buried at La Reunion Cemetery, however, is a colonist or one of their descendants:

Grave of Samuel Krause, an uncle of Bonnie Parker; Bonnie herself was once interred here before being moved to Crown Hill Cemetery

But what of the ghost town itself? Other than the cemetery, does anything from La Reunion still survive? I'm going to let you in on a little secret:

Front steps leading to the remains of the last remaining La Reunion house

Past these steps, on a sidewalk that is covered in dirt and choked with thick vegetation, there once stood a La Reunion colony house that survived all of its neighbors until it collapsed sometime in the 1930s. Even so, something still remains at the old homestead:

Small brick tower, part of the last La Reunion house

Where exactly are the remains of this ghost town house located? The precise location was known to a few schoolchildren in the area who would play there after school; supposedly there are a few more of these sites hiding throughout La Reunion. One of the children who knew of these ruins finally started spreading the word, and eventually the story reached me by means of the Internet, so I travelled to the La Reunion site and did a little exploring of my own until I found this. So I don't feel right just giving up the location, since a handful of Dallasites have made this their little secret. If you wish to find these ruins on your own, I offer this advice: Study the layout and history of La Reunion, drive and hike through the site of the old French colony, and keep your eyes open at all times.

One of these days, however, these last remnants of La Reunion may be swept away. The DAR memorial and the cemetery are safe, but there's a lot of money pouring into this area of Dallas, and with that money comes plans to redevelop the whole neighborhood. When that happens, the ghost town of La Reunion - which managed to survive all of its rivals for all these years - may be eradicated once and for all. So by all means, please go and explore this novel little corner of forgotten Texas history while you have the chance.

Happy Thanksgiving, everybody!

All the other towns have pretty much assimilated into Dallas without leaving any trace of their former selves, and that makes the story of La Reunion all the more fascinating to me. Settled in 1854 and officially founded the next year to serve as a communal society operating on the socio-economic principles espoused by French philosopher Francois Marie Charles Fourier, the town sat on the Trinity River, three miles west of what used to be the village of Dallas. 200 immigrants from France, Belgium, and Switzerland got the project started, and while some of the colonists moved on, there were enough new arrivals to keep La Reunion operating for approximately 18 months, with the population peaking at 350 in late 1856.

La Reunion had everything working against it. The limestone soil proved to be a constant frustration for agriculturists. The colony was plagued with ineffective leadership and disorganization, not to mention financial insolvency. On January 28, 1857, La Reunion was officially dissolved. A few holdouts purchased land on the La Reunion tract and made the site their permanent home, but most colonists either returned to Europe or resettled in Dallas, San Antonio, or New Orleans.

When Dallas expanded westward and swallowed what was left of La Reunion, the townsite was excavated for lime used in the manufacture of concrete, which was sorely needed by the growing city; in fact, the site of La Reunion was incorporated as the town of Cement City for a few decades. Reunion Tower and the now-demolished Reunion Arena were named after the old colony, but at first glance, there seems to be nothing left of La Reunion; instead, there are houses, schools, buinesses, and a golf course in Stevens Park. Walk through the golf course, and you'll see a stone erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1924.

Granite DAR memorial at the Stevens Park golf course, marking the La Reunion site

The DAR memorial is a lovely tribute, but obviously not part of the original colony. For that, travel over to L.G. Pinkston High School at 3345 Fish Trap Road in Dallas and face northwest from the school. You'll be looking at a housing development, and right next to it there is a semi-neglected cemetery that was once known as Fish Trap Cemetery, but a historical marker within the chainlink fence surrounding the cemetery proclaims this the burial site for some of the La Reunion colonists:

Historical marker for La Reunion Cemetery on Fish Trap Road in Dallas

According to a Dallas Morning News article on La Reunion Cemetery, there has been considerable difficulty finding which agency is responsible for the cemetery's upkeep. Some determined volunteers are doing what they can to tend to the cemetery, and once in a while, some enterprising ghost town chaser finds his way into the cemetery as well. Here are some of the graves at the site:

Tombstone for botanist Julien Reverchon and his wife Marie, both La Reunion colonists; Reverchon Park in Dallas is named in Julien's honor

Broken grave marker for Michel Reverchon, son of Julien and Marie Reverchon

Francois Santerre, one of the most prominent La Reunion colonists, is buried here with his wife, Marie

Not everyone buried at La Reunion Cemetery, however, is a colonist or one of their descendants:

Grave of Samuel Krause, an uncle of Bonnie Parker; Bonnie herself was once interred here before being moved to Crown Hill Cemetery

But what of the ghost town itself? Other than the cemetery, does anything from La Reunion still survive? I'm going to let you in on a little secret:

Front steps leading to the remains of the last remaining La Reunion house

Past these steps, on a sidewalk that is covered in dirt and choked with thick vegetation, there once stood a La Reunion colony house that survived all of its neighbors until it collapsed sometime in the 1930s. Even so, something still remains at the old homestead:

Small brick tower, part of the last La Reunion house

Where exactly are the remains of this ghost town house located? The precise location was known to a few schoolchildren in the area who would play there after school; supposedly there are a few more of these sites hiding throughout La Reunion. One of the children who knew of these ruins finally started spreading the word, and eventually the story reached me by means of the Internet, so I travelled to the La Reunion site and did a little exploring of my own until I found this. So I don't feel right just giving up the location, since a handful of Dallasites have made this their little secret. If you wish to find these ruins on your own, I offer this advice: Study the layout and history of La Reunion, drive and hike through the site of the old French colony, and keep your eyes open at all times.

One of these days, however, these last remnants of La Reunion may be swept away. The DAR memorial and the cemetery are safe, but there's a lot of money pouring into this area of Dallas, and with that money comes plans to redevelop the whole neighborhood. When that happens, the ghost town of La Reunion - which managed to survive all of its rivals for all these years - may be eradicated once and for all. So by all means, please go and explore this novel little corner of forgotten Texas history while you have the chance.

Happy Thanksgiving, everybody!

Sunday, November 20, 2011

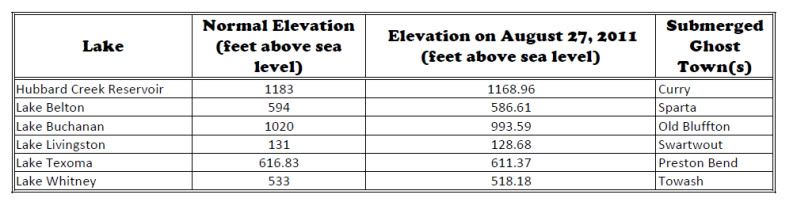

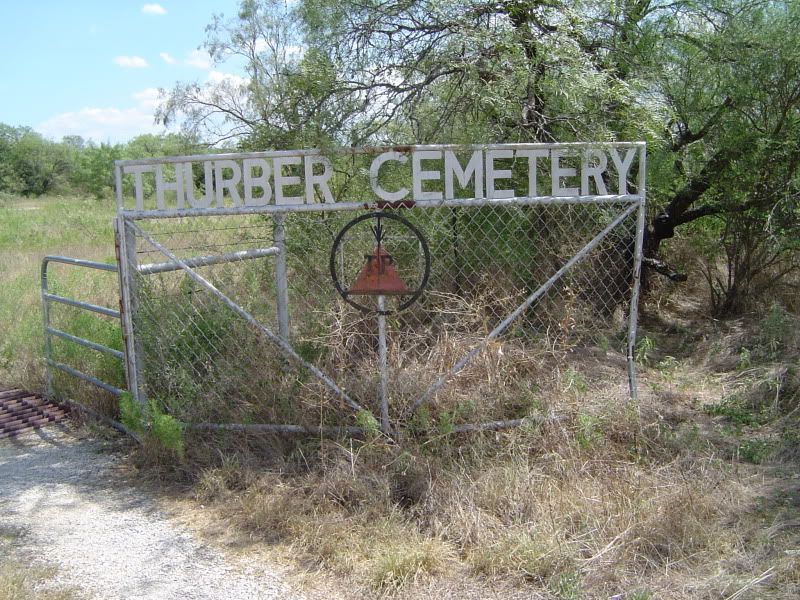

News story on Old Bluffton site at Lake Buchanan and looting at Lake Whitney

I was in Austin over the weekend, and I really wanted to make a day trip to Lake Buchanan to check out the once-submerged ghost town of Old Bluffton. It just wasn't in the cards this time around, but Associated Press reporters were able to visit the site for a news story. Next time I'm in the Austin area, no more excuses - I'm heading to Old Bluffton, and you know I'll be more than happy to share pictures with you.

The AP article also covers efforts by the Army Corps of Engineers to curtail looting of Native American sites at Lake Whitney that have long been submerged. I condemn the theft of artifacts from these sites, and if by any chance you did remove some of these relics from the Lake Whitney area, what were you thinking? It's the same as if someone ransacked your family plot in search of jewelry or maybe a few gold teeth. Enough, already. My only interest in the Lake Whitney area is in the remains of the submerged ghost town of Towash, nothing more. (D.S., please e-mail me when you can - tried to reach you without success.)

The AP article also covers efforts by the Army Corps of Engineers to curtail looting of Native American sites at Lake Whitney that have long been submerged. I condemn the theft of artifacts from these sites, and if by any chance you did remove some of these relics from the Lake Whitney area, what were you thinking? It's the same as if someone ransacked your family plot in search of jewelry or maybe a few gold teeth. Enough, already. My only interest in the Lake Whitney area is in the remains of the submerged ghost town of Towash, nothing more. (D.S., please e-mail me when you can - tried to reach you without success.)

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Camden (Gregg County) - January 2011 photos

First things first, I have to give credit to photographer Maryanne Gobble for bringing to my attention a vanishing townsite in East Texas with her photo essay of Camden on the Texas Escapes website, which has a sizable archive of ghost towns complete with lots of pictures.

I was visiting my parents in Mineola back in January of this year, and spurred on by Gobble's photos of what were supposed to be the remains of a very old settlement in Texas, I made a day trip southeast of Longview to the community of Easton, which sits south of the Sabine River in southeastern Gregg County. Once in Easton, I followed the directions supplied by Gobble and turned onto a road that didn't seem to have a name, leading north towards the Sabine River into a clearing dominated by a natural gas pipeline. No road signs, no markers of any kind. Just a forlorn cemetery to my right and a forest with two crumbling houses to my left. Welcome to Camden, aka Walling's Ferry - one of the earliest white settlements in the region.

Sometime in the late 1820s or early 1830s, when Texas was still under Mexican rule, John Walling made his way down to the Sabine River and established a ferry crossing named after himself. The Mexican government licensed Walling's Ferry in the early 1830s. As it was one of the few settled areas in East Texas back in those days, many travelers availed themselves of the ferry when they arrived at Texas, and Sam Houston reportedly stopped at Walling's Ferry when he first entered Texas in 1832. After Texas gained its independence, Walling's Ferry was formally established as a townsite in 1844, the same year that Enoch Hays built an eight-room, two-story tavern at the townsite to accommodate the flow of travelers (but if you wanted a bath, your only option was a dunk in the Sabine River). For many years, Walling's Ferry was also known as Camden, and the town officially changed its name to Camden in 1847 when it obtained its own post office. In those days, Camden was part of Rusk County; the original boundaries of Gregg County, where Camden now sits, weren't drawn until 1873.

Steamboats started coming up the Sabine as far as Camden, which boosted trade for the town; a few plantations at Camden grew cotton and shipped it down the river. This meant that Camden was getting rich, and getting rich quickly - and Enoch Hays was getting a sizable portion of that cash flow. In addition to the tavern, Hays sold cotton grown on his own plantation and took over John Walling's ferry operation in 1850 when Walling left Camden for North Carolina. During the 1850s, Camden featured the Hays tavern/hotel, the post office, a Presbyterian church, a jug factory, a Masonic lodge, and several stores and saloons in addition to the cotton plantations. A telegraph line was also installed at Camden in 1854, one of the first such lines established in Texas; it enabled Camden to coordinate steamboat shipments with Galveston and New Orleans. Although I haven't found any population estimates for Camden during its heyday, Sam Houston made several trips to Camden to attend political rallies, and when Democratic Presidential nominee James Buchanan visited Camden in 1856 for a party function (complete with barbecue), he addressed 10,000 people at the town. Considering that the 1850 census of Rusk County yielded a population of 8,148, this was no small achievement.

Camden's downfall apparently came while the Civil War raged. During this time, Camden was used as a shipping depot for Confederate units to the east, which normally wasn't a problem except that a drought apparently lowered the water level of the Sabine enough to make riverboat navigation problematic. The resulting stagnant pools of water in the river bottoms would prove to be excellent breeding grounds for mosquitoes, who then inflicted themselves upon the townfolk of Camden, bringing malaria and yellow fever with them. In addition, while other East Texas towns replaced their own ferry services with navigable bridges, Camden never followed suit. With new railroad lines being built throughout the region to keep East Texas connected with the rest of the world, the townfolk of Camden simply started packing up and heading out for greener pastures. According to the TSHA, one traveler who visited Camden after the end of the Civil War described the remaining holdouts as "notably inert and melancholy." When the community of Iron Bridge was fully established six miles south of Longview, it reportedly attracted even more Camden residents to resettle there. The post office shut down for good on December 13, 1872, and Camden quickly started disappearing from state maps. Those who were left behind - many of them freed slaves who used to work on Camden's cotton plantations - eventually relocated to the newly-formed sawmill town of Easton, conveniently located on a new stretch of railroad tracks laid down by the Longview and Sabine Valley Railroad Company in 1878. At this point, Camden had become an absolute ghost.

Today, these are the only remains of the once-bustling town of Camden:

A view of Camden Cemetery, with the natural gas pipeline clearly visible in what used to be the middle of town

The Waldron family plot at Camden Cemetery

Shattered tombstones at Camden Cemetery; the discovery of shotgun shells nearby suggests vandalism

Collapsed remains of a wooden house at Camden

An old well behind the wooden house

I call this collapsing house the "Camden White House" for want of a better name

Still life within the kitchen of the Camden White House

Abandoned furniture and debris in the living room of the Camden White House

It turns out that the January 17, 2011 edition of the Tyler Morning Telegraph published its own article on the history of Camden as well as the development of Easton; it's definitely worth a look. There is now a push by Walter Ward, mayor of Easton, to have the cemetery at Camden officially recognized by Texas as a historical site. I wish him the best of luck.

And Iron Bridge? The irony is that Iron Bridge not only became a ghost town - all traces of the town appear to have vanished completely from the face of the earth, while just enough of Camden remained to be rediscovered by Texas ghost town enthusiasts today.

I was visiting my parents in Mineola back in January of this year, and spurred on by Gobble's photos of what were supposed to be the remains of a very old settlement in Texas, I made a day trip southeast of Longview to the community of Easton, which sits south of the Sabine River in southeastern Gregg County. Once in Easton, I followed the directions supplied by Gobble and turned onto a road that didn't seem to have a name, leading north towards the Sabine River into a clearing dominated by a natural gas pipeline. No road signs, no markers of any kind. Just a forlorn cemetery to my right and a forest with two crumbling houses to my left. Welcome to Camden, aka Walling's Ferry - one of the earliest white settlements in the region.

Sometime in the late 1820s or early 1830s, when Texas was still under Mexican rule, John Walling made his way down to the Sabine River and established a ferry crossing named after himself. The Mexican government licensed Walling's Ferry in the early 1830s. As it was one of the few settled areas in East Texas back in those days, many travelers availed themselves of the ferry when they arrived at Texas, and Sam Houston reportedly stopped at Walling's Ferry when he first entered Texas in 1832. After Texas gained its independence, Walling's Ferry was formally established as a townsite in 1844, the same year that Enoch Hays built an eight-room, two-story tavern at the townsite to accommodate the flow of travelers (but if you wanted a bath, your only option was a dunk in the Sabine River). For many years, Walling's Ferry was also known as Camden, and the town officially changed its name to Camden in 1847 when it obtained its own post office. In those days, Camden was part of Rusk County; the original boundaries of Gregg County, where Camden now sits, weren't drawn until 1873.

Steamboats started coming up the Sabine as far as Camden, which boosted trade for the town; a few plantations at Camden grew cotton and shipped it down the river. This meant that Camden was getting rich, and getting rich quickly - and Enoch Hays was getting a sizable portion of that cash flow. In addition to the tavern, Hays sold cotton grown on his own plantation and took over John Walling's ferry operation in 1850 when Walling left Camden for North Carolina. During the 1850s, Camden featured the Hays tavern/hotel, the post office, a Presbyterian church, a jug factory, a Masonic lodge, and several stores and saloons in addition to the cotton plantations. A telegraph line was also installed at Camden in 1854, one of the first such lines established in Texas; it enabled Camden to coordinate steamboat shipments with Galveston and New Orleans. Although I haven't found any population estimates for Camden during its heyday, Sam Houston made several trips to Camden to attend political rallies, and when Democratic Presidential nominee James Buchanan visited Camden in 1856 for a party function (complete with barbecue), he addressed 10,000 people at the town. Considering that the 1850 census of Rusk County yielded a population of 8,148, this was no small achievement.

Camden's downfall apparently came while the Civil War raged. During this time, Camden was used as a shipping depot for Confederate units to the east, which normally wasn't a problem except that a drought apparently lowered the water level of the Sabine enough to make riverboat navigation problematic. The resulting stagnant pools of water in the river bottoms would prove to be excellent breeding grounds for mosquitoes, who then inflicted themselves upon the townfolk of Camden, bringing malaria and yellow fever with them. In addition, while other East Texas towns replaced their own ferry services with navigable bridges, Camden never followed suit. With new railroad lines being built throughout the region to keep East Texas connected with the rest of the world, the townfolk of Camden simply started packing up and heading out for greener pastures. According to the TSHA, one traveler who visited Camden after the end of the Civil War described the remaining holdouts as "notably inert and melancholy." When the community of Iron Bridge was fully established six miles south of Longview, it reportedly attracted even more Camden residents to resettle there. The post office shut down for good on December 13, 1872, and Camden quickly started disappearing from state maps. Those who were left behind - many of them freed slaves who used to work on Camden's cotton plantations - eventually relocated to the newly-formed sawmill town of Easton, conveniently located on a new stretch of railroad tracks laid down by the Longview and Sabine Valley Railroad Company in 1878. At this point, Camden had become an absolute ghost.

Today, these are the only remains of the once-bustling town of Camden:

A view of Camden Cemetery, with the natural gas pipeline clearly visible in what used to be the middle of town

The Waldron family plot at Camden Cemetery

Shattered tombstones at Camden Cemetery; the discovery of shotgun shells nearby suggests vandalism

Collapsed remains of a wooden house at Camden

An old well behind the wooden house

I call this collapsing house the "Camden White House" for want of a better name

Still life within the kitchen of the Camden White House

Abandoned furniture and debris in the living room of the Camden White House

It turns out that the January 17, 2011 edition of the Tyler Morning Telegraph published its own article on the history of Camden as well as the development of Easton; it's definitely worth a look. There is now a push by Walter Ward, mayor of Easton, to have the cemetery at Camden officially recognized by Texas as a historical site. I wish him the best of luck.

And Iron Bridge? The irony is that Iron Bridge not only became a ghost town - all traces of the town appear to have vanished completely from the face of the earth, while just enough of Camden remained to be rediscovered by Texas ghost town enthusiasts today.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Belcherville (Montague County) - May 2010/October 2011 photos

When I first started my personal ghost town project in May 2010, the first townsite I visited was that of Belcherville, which is located a short drive west of Nocona in Montague County in northern Texas. There was no real strategy for visiting Belcherville first; I was on my way north to Oklahoma City when I decided to make a side trip west of Interstate 35 on Highway 82 and visit a couple of ghost towns that T. Lindsay Baker had documented in his book Ghost Towns of Texas. Six miles west of Nocona, I turned north on FM 1816 and followed it up for about a quarter mile, and there it was.

Belcherville intrigued me so much during my short visit that I knew I'd have to come back someday, which I finally did in October 2011. During my first visit, it was just me, my trusty camera, and Baker's book in the front seat. Since then, I've taken advantage of various Web resources, satellite maps, and various accounts from others who have visited Belcherville or even lived there in the past. I've had to change many of my first assumptions of the ghost town as a result, and my appreciation for this abandoned town has grown significantly. Amanda Warr, editor of The Squawker, has described Belcherville as "a photographer's oasis of gutted old structures, abandoned homes, and overgrowth of purple sage, mesquite and spindly live oaks." Frankly, I can't top her description of the ghost town by myself - I'd better let my photos do most of the talking.

A short bit of background first. Belcherville, established in 1887 as part of a land promotion enterprise by Alex and John Belcher, enjoyed a short but happy boom period during which the population grew to at least 2,000, with thirty businesses serving the population. The Belcher brothers laid out the townsite apparently in anticipation of the extension of the Gainesville, Henrietta, and Western Railway. Indeed, the destruction of nearby Red River Station by a tornado in 1890 caused the denizens of that town to move further down the tracks to resettle in Belcherville, leaving Red River Station to become a ghost town in its own right.

The details of Belcherville's demise are a bit murky. The railroad eventually extended out to the still-active town of Henrietta, a few miles east of Wichita Falls on Highway 82, and this drew away some of Belcherville's townfolk; but what really brought Belcherville to its knees were a couple of fires that gutted the town. In Ghost Towns of Texas, Baker gives the date for the first fire as February 6, 1893, but the Texas State Historical Association claims that the fires erupted shortly after World War I. Oral tradition from some of the people who stayed at Belcherville states that the business district was burned down by people from the other side of town, so someone from the business district retaliated by burning down whatever was left - in other words, Belcherville self-destructed. Only a few of the buildings were rebuilt, because everyone was headed off to greener pastures in Nocona or Henrietta. In 1930, there were only 85 people and five businesses left in Belcherville; in 2000, only 34 people still resided at Belcherville.

And what does Belcherville look like today? I mentioned photos, so here goes:

A former gas station and post office at the heart of Belcherville; once operated by the Blevins family

The entrance foyer to the abandoned Belcherville Church of Christ, which collapsed sometime after 1992

Another view of the ruins of Belcherville Church of Christ

I've been told that the church sanctuary still contained pews, hymnals, and various other sundries before the roof collapsed. Want to excavate any of these from underneath the roof? You're braver than I am. Bring a first-aid kit, and I hope you like grasshoppers...

Exterior shot of Belcherville Baptist Church at the intersection of Belcher Avenue and Bonham Street, now hidden behind trees and foliage

Interior of Belcherville Baptist Church's sanctuary with minister's pulpit

When I first discovered this abandoned school, I regarded it as another church. Then I found older photographs and testimonials from former students of Belcherville High School that seemed to confirm that this was a school building instead of a church. Not true, according to a former resident of Belcherville; this is a church after all. One more reason why studying history is so important - it's so fragile.

The abandoned Manley house in Belcherville on Elm Street

Abandoned furniture and debris inside the Manley house; the doorway leads to the deteriorating bathroom

A word of caution - when I explored the Manley house, it groaned and creaked whenever the winds picked up. This house may not remain upright by the time you make it out to Belcherville, so take advantage of the cooler autumn temperatures and see it now while it lasts.

Abandoned Belcherville gas station and grocery store, once operated by the Vannoy family, right off of Highway 82

Intriguing stone ruins on the extreme western edge of Belcherville, now on private property

Sign near the front gate to Belcherville Cemetery, on Crenshaw Road west of the town center

Handsome tombstone of Belcherville Freemason V.D. Cranford

Primitive stone grave of John W. Campbell with hand-carved grave marker

There are many gravestones at Belcherville Cemetery where either the letters have weathered away or there never was any inscription in the first place. This plot, however, is the most isolated of all the plots at Belcherville Cemetery - and, in my estimation, one of the most poignant cemetery plots I've seen:

"Unknown Cowboy" buried at Belcherville Cemetery - unknown, but definitely not unloved

I hope this photo essay has inspired you to make your own trip to Belcherville and visit these sites on your own. Be sensible, be safe, and by all means, enjoy.

PS - Amanda, if you're reading this, I have yet to visit Big Fatty's Spankin' Shack in Valley View. I'm a big fan of Clark's Outpost in Tioga, myself. But maybe I'll take the Big Fatty's challenge next time I'm in the neighborhood.

Belcherville intrigued me so much during my short visit that I knew I'd have to come back someday, which I finally did in October 2011. During my first visit, it was just me, my trusty camera, and Baker's book in the front seat. Since then, I've taken advantage of various Web resources, satellite maps, and various accounts from others who have visited Belcherville or even lived there in the past. I've had to change many of my first assumptions of the ghost town as a result, and my appreciation for this abandoned town has grown significantly. Amanda Warr, editor of The Squawker, has described Belcherville as "a photographer's oasis of gutted old structures, abandoned homes, and overgrowth of purple sage, mesquite and spindly live oaks." Frankly, I can't top her description of the ghost town by myself - I'd better let my photos do most of the talking.

A short bit of background first. Belcherville, established in 1887 as part of a land promotion enterprise by Alex and John Belcher, enjoyed a short but happy boom period during which the population grew to at least 2,000, with thirty businesses serving the population. The Belcher brothers laid out the townsite apparently in anticipation of the extension of the Gainesville, Henrietta, and Western Railway. Indeed, the destruction of nearby Red River Station by a tornado in 1890 caused the denizens of that town to move further down the tracks to resettle in Belcherville, leaving Red River Station to become a ghost town in its own right.

The details of Belcherville's demise are a bit murky. The railroad eventually extended out to the still-active town of Henrietta, a few miles east of Wichita Falls on Highway 82, and this drew away some of Belcherville's townfolk; but what really brought Belcherville to its knees were a couple of fires that gutted the town. In Ghost Towns of Texas, Baker gives the date for the first fire as February 6, 1893, but the Texas State Historical Association claims that the fires erupted shortly after World War I. Oral tradition from some of the people who stayed at Belcherville states that the business district was burned down by people from the other side of town, so someone from the business district retaliated by burning down whatever was left - in other words, Belcherville self-destructed. Only a few of the buildings were rebuilt, because everyone was headed off to greener pastures in Nocona or Henrietta. In 1930, there were only 85 people and five businesses left in Belcherville; in 2000, only 34 people still resided at Belcherville.

And what does Belcherville look like today? I mentioned photos, so here goes:

A former gas station and post office at the heart of Belcherville; once operated by the Blevins family

The entrance foyer to the abandoned Belcherville Church of Christ, which collapsed sometime after 1992

Another view of the ruins of Belcherville Church of Christ

I've been told that the church sanctuary still contained pews, hymnals, and various other sundries before the roof collapsed. Want to excavate any of these from underneath the roof? You're braver than I am. Bring a first-aid kit, and I hope you like grasshoppers...

Exterior shot of Belcherville Baptist Church at the intersection of Belcher Avenue and Bonham Street, now hidden behind trees and foliage

Interior of Belcherville Baptist Church's sanctuary with minister's pulpit

When I first discovered this abandoned school, I regarded it as another church. Then I found older photographs and testimonials from former students of Belcherville High School that seemed to confirm that this was a school building instead of a church. Not true, according to a former resident of Belcherville; this is a church after all. One more reason why studying history is so important - it's so fragile.

The abandoned Manley house in Belcherville on Elm Street

Abandoned furniture and debris inside the Manley house; the doorway leads to the deteriorating bathroom

A word of caution - when I explored the Manley house, it groaned and creaked whenever the winds picked up. This house may not remain upright by the time you make it out to Belcherville, so take advantage of the cooler autumn temperatures and see it now while it lasts.

Abandoned Belcherville gas station and grocery store, once operated by the Vannoy family, right off of Highway 82

Intriguing stone ruins on the extreme western edge of Belcherville, now on private property

Sign near the front gate to Belcherville Cemetery, on Crenshaw Road west of the town center

Handsome tombstone of Belcherville Freemason V.D. Cranford

Primitive stone grave of John W. Campbell with hand-carved grave marker

There are many gravestones at Belcherville Cemetery where either the letters have weathered away or there never was any inscription in the first place. This plot, however, is the most isolated of all the plots at Belcherville Cemetery - and, in my estimation, one of the most poignant cemetery plots I've seen:

"Unknown Cowboy" buried at Belcherville Cemetery - unknown, but definitely not unloved

I hope this photo essay has inspired you to make your own trip to Belcherville and visit these sites on your own. Be sensible, be safe, and by all means, enjoy.

PS - Amanda, if you're reading this, I have yet to visit Big Fatty's Spankin' Shack in Valley View. I'm a big fan of Clark's Outpost in Tioga, myself. But maybe I'll take the Big Fatty's challenge next time I'm in the neighborhood.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Terlingua Chili Cookoff - November 3-5, 2011

I reckon any Texas ghost town blog worth its salt needs to take a moment to call attention to the upcoming 45th Annual Original Terlingua International Frank X. Tolbert - Wick Fowler Championship Chili Cookoff, which is taking place on November 3-5, 2011 in the Brewster County ghost town of Terlingua. Although the county is still under a burn ban due to the ongoing drought, the Chili Cookoff has been granted a waiver provided a few safety measures are obeyed for safety reasons.

Wish I could be there, myself. I love a good bowl of chili.

Then again, here's something to consider: According to our friends at the TSHA, Terlingua boasted a population of 267 in 2000 as well as 44 businesses - far removed from its utter desolation in the early 1960s. Is Terlingua on the verge of shedding its "ghost town" status, provided that the upward trend continues?

Wish I could be there, myself. I love a good bowl of chili.

Then again, here's something to consider: According to our friends at the TSHA, Terlingua boasted a population of 267 in 2000 as well as 44 businesses - far removed from its utter desolation in the early 1960s. Is Terlingua on the verge of shedding its "ghost town" status, provided that the upward trend continues?

Monday, October 10, 2011

A Ghost Town Explorer's Checklist

Not that long ago, I was discussing Texas ghost towns with someone who told me that her son had gotten excited about paying a visit to his first-ever ghost town, and apparently I was one of his influences. I am indeed touched by this. After discussing preparations for the trip, I realized the list I came up with might benefit any of you who are also thinking of taking that first trip to Terlingua or Luckenbach or some other ghost town destination in Texas.

That said, here's a list of what I consider must-haves for first-time adventurers:

BOOK OF COUNTY MAPS

Don't rely on a simple traveler's atlas or even one of those travel maps that you can pick up at a convenience store or visitor's welcome center - exploring ghost towns in Texas calls for a really good county map book that shows all the highways, byways, county roads, gravel roads, pipelines, and all that. I've been using a laminated Texas county map book from MAPSCO that has been indispensible in my searches. The books Ghost Towns of Texas and More Ghost Towns of Texas by T. Lindsay Baker provide driving directions to select ghost town sites throughout Texas as well as some really good history on each site. Baker's books and the county map book always come with me on every trip.

BOTTLED WATER

Never, never, never underestimate the importance of hydration. When you hike a couple of miles into the middle of nowhere during a 100-degree summer afternoon in Texas, you're really going to miss having a cold one-liter bottle of water by your side - provided you're not already suffering from dehydration or heatstroke (or both). Seriously. Take an insulated shopping bag with a couple of cold one-liters. Or grab yourself some reusable bottles from SIGG or Klean Kanteen or whatever your favorite brand is. Or your can splurge a little and invest in a Camelbak system or something similar that you wear on your shoulders.

MACHETE

For cutting through the occasional clump of brush or thicket or reenacting scenes from Robert Rodriguez films just for fun (as long as nobody gets hurt). You won't need this everywhere, but it's good to keep this handy just in case. You can always leave it in your vehicle.

WALKING STICK

If you're in tall grass, by the lake, in a marsh, or just someplace unfamiliar to you, best to keep a good walking stick at your side. Use it to test the ground in front of you for quicksand, critters, or other assorted hazards.

CELLPHONE

Can you hear me now? It always pays to have law enforcement or AAA at the push of a button if something should happen during your travels, and a surprising number of ghost towns do have some form of cellphone reception. No, you're probably not going to get 4G speeds in the middle of Indianola or Bugtussle, but that's okay.

FIRST AID KIT

Self-explanatory.

Now for a list of "optionals" you might consider bringing along:

COMPASS

A simple five-dollar compass that you can get at any Wal-Mart, for when it's time to blaze new trails.

PEDOMETER

Nothing fancy, just something that tracks how far you've actually walked from your car. Walking's good exercise, and most ghost towns have plenty of fresh air.

SNACKS

I have always considered a can of Pringle's chips to be a godsend after a lengthy hike. Water is vital, but if you've been sweating, you'll want to start replacing your salts, too. There's probably more nutritious ways to do it than Pringle's, so if you want to take along some trail mix, fresh fruit, Beer Nuts, or whatever keeps you going, use what works best for you.

FIREARM

A little discretion is warranted here, especially since the ghost town adventurer is strongly encouraged to obey all Federal, state, and local gun laws. In addition, use your head - if the county you're in is under a burn ban, exercise extreme caution. The only reason I mention firearms is that I've heard from one friend who got shot at merely for visiting a remote cemetery in the Texas Hill Country. If you encounter a hostile boar or some sort of ornery critter, you might need more than just a machete. If you object to carrying a firearm, I understand. But please be safe no matter what you decide.

CAMERA

Surely you're not going to run off to some abandoned town in the Panhandle or near the Mexican border without snapping a few pictures to share with your grandchildren?

And finally, something to take along that some of you might consider strictly optional, but others will consider the most important of all:

A FRIEND

So far, I have visited some three dozen ghost towns throughout Texas since May 2010, and I have always travelled alone. I'd like to take a trip sometime with a friend, someone who can provide good company while making sure I don't get myself in too deep. I've had a couple of folks who have offered to ride shotgun with me into the forgotten towns of Texas - you know who you are, and I thank you. It'll be fun, I promise.

That said, here's a list of what I consider must-haves for first-time adventurers:

BOOK OF COUNTY MAPS

Don't rely on a simple traveler's atlas or even one of those travel maps that you can pick up at a convenience store or visitor's welcome center - exploring ghost towns in Texas calls for a really good county map book that shows all the highways, byways, county roads, gravel roads, pipelines, and all that. I've been using a laminated Texas county map book from MAPSCO that has been indispensible in my searches. The books Ghost Towns of Texas and More Ghost Towns of Texas by T. Lindsay Baker provide driving directions to select ghost town sites throughout Texas as well as some really good history on each site. Baker's books and the county map book always come with me on every trip.

BOTTLED WATER

Never, never, never underestimate the importance of hydration. When you hike a couple of miles into the middle of nowhere during a 100-degree summer afternoon in Texas, you're really going to miss having a cold one-liter bottle of water by your side - provided you're not already suffering from dehydration or heatstroke (or both). Seriously. Take an insulated shopping bag with a couple of cold one-liters. Or grab yourself some reusable bottles from SIGG or Klean Kanteen or whatever your favorite brand is. Or your can splurge a little and invest in a Camelbak system or something similar that you wear on your shoulders.

MACHETE

For cutting through the occasional clump of brush or thicket or reenacting scenes from Robert Rodriguez films just for fun (as long as nobody gets hurt). You won't need this everywhere, but it's good to keep this handy just in case. You can always leave it in your vehicle.

WALKING STICK

If you're in tall grass, by the lake, in a marsh, or just someplace unfamiliar to you, best to keep a good walking stick at your side. Use it to test the ground in front of you for quicksand, critters, or other assorted hazards.

CELLPHONE

Can you hear me now? It always pays to have law enforcement or AAA at the push of a button if something should happen during your travels, and a surprising number of ghost towns do have some form of cellphone reception. No, you're probably not going to get 4G speeds in the middle of Indianola or Bugtussle, but that's okay.

FIRST AID KIT

Self-explanatory.

Now for a list of "optionals" you might consider bringing along:

COMPASS

A simple five-dollar compass that you can get at any Wal-Mart, for when it's time to blaze new trails.

PEDOMETER

Nothing fancy, just something that tracks how far you've actually walked from your car. Walking's good exercise, and most ghost towns have plenty of fresh air.

SNACKS

I have always considered a can of Pringle's chips to be a godsend after a lengthy hike. Water is vital, but if you've been sweating, you'll want to start replacing your salts, too. There's probably more nutritious ways to do it than Pringle's, so if you want to take along some trail mix, fresh fruit, Beer Nuts, or whatever keeps you going, use what works best for you.

FIREARM

A little discretion is warranted here, especially since the ghost town adventurer is strongly encouraged to obey all Federal, state, and local gun laws. In addition, use your head - if the county you're in is under a burn ban, exercise extreme caution. The only reason I mention firearms is that I've heard from one friend who got shot at merely for visiting a remote cemetery in the Texas Hill Country. If you encounter a hostile boar or some sort of ornery critter, you might need more than just a machete. If you object to carrying a firearm, I understand. But please be safe no matter what you decide.

CAMERA

Surely you're not going to run off to some abandoned town in the Panhandle or near the Mexican border without snapping a few pictures to share with your grandchildren?

And finally, something to take along that some of you might consider strictly optional, but others will consider the most important of all:

A FRIEND

So far, I have visited some three dozen ghost towns throughout Texas since May 2010, and I have always travelled alone. I'd like to take a trip sometime with a friend, someone who can provide good company while making sure I don't get myself in too deep. I've had a couple of folks who have offered to ride shotgun with me into the forgotten towns of Texas - you know who you are, and I thank you. It'll be fun, I promise.

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Marysville (Cooke County) - September 2011 photos

The ghost town of Marysville, TX is not for the inexperienced or the faint of heart.

For starters, Marysville is one of the most isolated ghost towns in North Texas. Not a single paved road leads into or out of this Cooke County town - it's all gravel roads no matter how you approach the town. The most direct route to Marysville is to take Farm to Market Road 2739 north from US 82 (just east of Muenster) and follow it up for about 3.7 miles until you run out of pavement. At this point, FM 2739 turns into County Road 417, which winds and twists for around five rickety miles north through fields and over dry creeks (not recommended at night) until you finally reach the townsite. Don't look for any road signs; instead, look for a little white Baptist church on the east side of CR 417.

There are only 15 people (at most) living in Marysville, and it takes a special breed of Texan to live here. The nearest building that resembles a store is a 30-minute drive away, so you learn to live off the land, make do with what you have, and plan your drives into town for supplies carefully. If you're the type that is used to hopping in the car and driving to the nearest 7-Eleven because you're in the mood for a Slurpee, Marysville is definitely not for you. The locals are friendly enough, but also wary of outsiders, and one of them apparently doesn't see any harm in letting a pack of barking dogs surround any unannounced visitors whether on foot or in their vehicles. Even if you don't encounter either people or dogs during your sojourn in Marysville, it may not be that uncommon to hear in the distance the shouts of hunters, the baying of hounds, and the roar of shotguns. Consider this a friendly advisory.

So, folks - guess where I was one cool September evening? Here's some photos from the trip to Marysville in Cooke County:

An abandoned store in Marysville off of CR 417; the front porch collapsed within the last decade

Another abandoned store, boarded up and buried a little deeper in the woods

Marysville Baptist Church, where worship services have been held since 1872

Detail of the Marysville Baptist Church sign

Ruins of an old Marysville house

A disused building that served as a church (and possibly as a Masonic lodge)

Front gate to Marysville Cemetery, the larger of two cemeteries at the townsite

A sample of the numerous gravesites in Marysville Cemetery, some of them over 150 years old

Tombstone of Marysville's most famous resident - Daniel Montague; surveyor, Texas state senator, and namesake of neighboring Montague County

By 1900, according to the Texas State Historical Association, Marysville had 250 residents, a drugstore, a livery stable, a district school, a post office, two churches, two grocery stores, two blacksmith shops, and two mercantile stores. The town served the needs of small farms in central Cooke County, and even after the Great Depression hit, Marysville continued on with a somewhat smaller population until December 1941, when Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor and America found itself in the middle of World War II.

A week or two after Pearl Harbor, the War Department swooped into Cooke County and purchased some 59,000 acres north, east, and south of Marysville from the local farmers, turning the tract of land into Camp Howze, which served as an infantry training site and POW camp for captured German soldiers. Marysville was relatively isolated from the rest of Cooke County by Camp Howze, but the $20 million that Washington, DC pumped into the camp helped fuel the local economy until the end of the war. In 1946, Camp Howze was declared surplus and completely dismantled, the land once again available for the original farmers to come back - but they never did.

Without either the farms or a military camp to keep Marysville afloat, the town withered. First to go was the post office. By 1980, all of the businesses in Maryville were defunct, with only Marysville Baptist Church surviving. Even then, however, there were some 70 people living at the townsite, but the number plummeted drastically over the next 20 years. The handful that stayed put at Marysville are making do the best they know how, with their scattered homesteads, their gravel roads, and the pervading stillness that is occasionally broken by the baying of hounds and the roar of shotguns.

For starters, Marysville is one of the most isolated ghost towns in North Texas. Not a single paved road leads into or out of this Cooke County town - it's all gravel roads no matter how you approach the town. The most direct route to Marysville is to take Farm to Market Road 2739 north from US 82 (just east of Muenster) and follow it up for about 3.7 miles until you run out of pavement. At this point, FM 2739 turns into County Road 417, which winds and twists for around five rickety miles north through fields and over dry creeks (not recommended at night) until you finally reach the townsite. Don't look for any road signs; instead, look for a little white Baptist church on the east side of CR 417.

There are only 15 people (at most) living in Marysville, and it takes a special breed of Texan to live here. The nearest building that resembles a store is a 30-minute drive away, so you learn to live off the land, make do with what you have, and plan your drives into town for supplies carefully. If you're the type that is used to hopping in the car and driving to the nearest 7-Eleven because you're in the mood for a Slurpee, Marysville is definitely not for you. The locals are friendly enough, but also wary of outsiders, and one of them apparently doesn't see any harm in letting a pack of barking dogs surround any unannounced visitors whether on foot or in their vehicles. Even if you don't encounter either people or dogs during your sojourn in Marysville, it may not be that uncommon to hear in the distance the shouts of hunters, the baying of hounds, and the roar of shotguns. Consider this a friendly advisory.

So, folks - guess where I was one cool September evening? Here's some photos from the trip to Marysville in Cooke County:

An abandoned store in Marysville off of CR 417; the front porch collapsed within the last decade

Another abandoned store, boarded up and buried a little deeper in the woods

Marysville Baptist Church, where worship services have been held since 1872

Detail of the Marysville Baptist Church sign

Ruins of an old Marysville house

A disused building that served as a church (and possibly as a Masonic lodge)

Front gate to Marysville Cemetery, the larger of two cemeteries at the townsite

A sample of the numerous gravesites in Marysville Cemetery, some of them over 150 years old

Tombstone of Marysville's most famous resident - Daniel Montague; surveyor, Texas state senator, and namesake of neighboring Montague County

By 1900, according to the Texas State Historical Association, Marysville had 250 residents, a drugstore, a livery stable, a district school, a post office, two churches, two grocery stores, two blacksmith shops, and two mercantile stores. The town served the needs of small farms in central Cooke County, and even after the Great Depression hit, Marysville continued on with a somewhat smaller population until December 1941, when Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor and America found itself in the middle of World War II.

A week or two after Pearl Harbor, the War Department swooped into Cooke County and purchased some 59,000 acres north, east, and south of Marysville from the local farmers, turning the tract of land into Camp Howze, which served as an infantry training site and POW camp for captured German soldiers. Marysville was relatively isolated from the rest of Cooke County by Camp Howze, but the $20 million that Washington, DC pumped into the camp helped fuel the local economy until the end of the war. In 1946, Camp Howze was declared surplus and completely dismantled, the land once again available for the original farmers to come back - but they never did.

Without either the farms or a military camp to keep Marysville afloat, the town withered. First to go was the post office. By 1980, all of the businesses in Maryville were defunct, with only Marysville Baptist Church surviving. Even then, however, there were some 70 people living at the townsite, but the number plummeted drastically over the next 20 years. The handful that stayed put at Marysville are making do the best they know how, with their scattered homesteads, their gravel roads, and the pervading stillness that is occasionally broken by the baying of hounds and the roar of shotguns.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

"Vanished" ghost towns

Every once in a while, a ghost town in Texas vanishes. It isn't swallowed by thick East Texas woods or submerged beneath a lake. It simply - POOF! - ceases to exist whatsoever. For want of a better term, I call these sites "vanished ghost towns."

In order for a ghost town to cling to "life," there must be some tangible remains of the old town still in existence. The Texas ghost towns of Jonesboro and Spivey are both hanging on by a thread with exactly one grave each, but sometimes not a single grave, not a single foundation, not even a bit of town masonry survives. That's when the ghost town in question has vanished once and for all.

The following is a short list of vanished ghost towns in Texas provided for your perusal. Enjoy.

ALABAMA (Houston County)

A former steamboat stop on the Trinity River, founded in the 1830s. On January 30, 1841, the Republic of Texas established Trinity College at Alabama, the first college anywhere in Texas. Alabama received its own post office in 1846, with A.T. Monroe as postmaster. The town apparently thrived for the next three decades as a shipping point for plantations in Houston County, but as the railroad slowly replaced the steamboat in the 1870s, Alabama's fortunes declined. The post office shut down in 1878, and most businesses and residents moved away from Alabama over the next decade. A school managed to operate in Alabama until 1897. By the time of the Great Depression, only a few scattered homes remained. The state established a Centennial Marker at the townsite in 1936, but today that site is a barren field on private property. Absolutely no remains of the old townsite appear to have survived.

JIMTOWN (Dallas County)

Those of you who ever stopped at Carl's Corner on I35E north of Hillsboro (before it turned into Willie's Place and then an oversized Petro) might appreciate the appeal of an older version of the basic concept that came to life during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes. James "Jim" Bumpas operated a store just south of Dallas when he wasn't farming, and the store obtained its own post office in 1878. After that, Jimtown became a hub for farmers who needed medicines (Bumpas was also a country pharmacist) or general provisions for home and hearth. Throughout the town's history, Jimtown featured a livery stable, a wagon yard, a school that served 100 pupils, and a "union church" that served the needs of Baptists, Methodists, and Cumberland Presbyterians all under one roof. The school eventually evolved into the Jimtown Independent School District, incorporated in 1914. However, the steady growth of Dallas could not be curtailed, and the school district merged with Dallas in 1925. Jim Bumpas died in 1903, and his store lost its post office and transformed into a feed store until the wrecking ball destroyed the heart and soul of Jimtown in 1940. Nothing is known to survive from the old town; even Jimtown Road (which ran in front of the store) was renamed Clarendon Drive. If anyone has knowledge of the fate of the union church at Jimtown, please let me know.

QUAKERTOWN (Denton County)

The story of Quakertown deserves special mention due to the fact that this town was intentionally eradicated because of racial tension and prejudice. Quakertown was established in 1870 as a black community right in the middle of white Denton, and it set up its first school in 1878. Not long afterwards, Quakertown boasted a decent collection of restaurants, stores, and churches. However, Denton's white establishment sniffed at Quakertown's dirt roads and unpainted houses, and the nearby College of Industrial Arts in Denton (now Texas Woman's University) felt its close proximity to Quakertown threatened its chances at accreditation. In addition, Denton's political heavyweights started eyeing the creek that flowed through Quakertown as an ideal location for a new city park. Blacks and whites alike who spoke out against the plan found themselves on the receiving end of violent threats, and in 1922, faster than you could say "Jim Crow," Denton's white population voted to annex Quakertown and thus eradicate it, moving or demolishing all houses and buildings at the townsite and creating the Denton Civic Center Park where Quakertown once stood. The park has since been renamed Quakertown Park, but don't bother looking for any trace of the old town there - it's completely gone. One old Quakertown house, however, has been relocated to the Historical Park of Denton County; it now serves as the Denton County African American Museum.

WHO'D THOUGHT IT (Hopkins County)

As one person described it, "a forgotten town with an unforgettable name." Who'd Thought It was apparently organized as a farming community sometime after 1900 just north of fellow ghost town Sandhill (or south - I've heard it both ways) on Farm Road 1536. The first store at Who'd Thought It was operated by one Levi Kearny, and at its height during World War II, the small town had two stores and a number of scattered houses, and the local children attended school at Sandhill. In my own search for the town, I have yet to find any remnants of this community with the funny name, and I haven't even found Who'd Thought It on any maps in the archives of Hopkins County. I have apparently found a few scant remnants of Sandhill as well as a map giving its location as just north of Farm Road 1536 east of Tira, but if anyone has some information about the locale and fate of Who'd Thought It, please share.

In order for a ghost town to cling to "life," there must be some tangible remains of the old town still in existence. The Texas ghost towns of Jonesboro and Spivey are both hanging on by a thread with exactly one grave each, but sometimes not a single grave, not a single foundation, not even a bit of town masonry survives. That's when the ghost town in question has vanished once and for all.

The following is a short list of vanished ghost towns in Texas provided for your perusal. Enjoy.

ALABAMA (Houston County)

A former steamboat stop on the Trinity River, founded in the 1830s. On January 30, 1841, the Republic of Texas established Trinity College at Alabama, the first college anywhere in Texas. Alabama received its own post office in 1846, with A.T. Monroe as postmaster. The town apparently thrived for the next three decades as a shipping point for plantations in Houston County, but as the railroad slowly replaced the steamboat in the 1870s, Alabama's fortunes declined. The post office shut down in 1878, and most businesses and residents moved away from Alabama over the next decade. A school managed to operate in Alabama until 1897. By the time of the Great Depression, only a few scattered homes remained. The state established a Centennial Marker at the townsite in 1936, but today that site is a barren field on private property. Absolutely no remains of the old townsite appear to have survived.

JIMTOWN (Dallas County)

Those of you who ever stopped at Carl's Corner on I35E north of Hillsboro (before it turned into Willie's Place and then an oversized Petro) might appreciate the appeal of an older version of the basic concept that came to life during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes. James "Jim" Bumpas operated a store just south of Dallas when he wasn't farming, and the store obtained its own post office in 1878. After that, Jimtown became a hub for farmers who needed medicines (Bumpas was also a country pharmacist) or general provisions for home and hearth. Throughout the town's history, Jimtown featured a livery stable, a wagon yard, a school that served 100 pupils, and a "union church" that served the needs of Baptists, Methodists, and Cumberland Presbyterians all under one roof. The school eventually evolved into the Jimtown Independent School District, incorporated in 1914. However, the steady growth of Dallas could not be curtailed, and the school district merged with Dallas in 1925. Jim Bumpas died in 1903, and his store lost its post office and transformed into a feed store until the wrecking ball destroyed the heart and soul of Jimtown in 1940. Nothing is known to survive from the old town; even Jimtown Road (which ran in front of the store) was renamed Clarendon Drive. If anyone has knowledge of the fate of the union church at Jimtown, please let me know.

QUAKERTOWN (Denton County)

The story of Quakertown deserves special mention due to the fact that this town was intentionally eradicated because of racial tension and prejudice. Quakertown was established in 1870 as a black community right in the middle of white Denton, and it set up its first school in 1878. Not long afterwards, Quakertown boasted a decent collection of restaurants, stores, and churches. However, Denton's white establishment sniffed at Quakertown's dirt roads and unpainted houses, and the nearby College of Industrial Arts in Denton (now Texas Woman's University) felt its close proximity to Quakertown threatened its chances at accreditation. In addition, Denton's political heavyweights started eyeing the creek that flowed through Quakertown as an ideal location for a new city park. Blacks and whites alike who spoke out against the plan found themselves on the receiving end of violent threats, and in 1922, faster than you could say "Jim Crow," Denton's white population voted to annex Quakertown and thus eradicate it, moving or demolishing all houses and buildings at the townsite and creating the Denton Civic Center Park where Quakertown once stood. The park has since been renamed Quakertown Park, but don't bother looking for any trace of the old town there - it's completely gone. One old Quakertown house, however, has been relocated to the Historical Park of Denton County; it now serves as the Denton County African American Museum.

WHO'D THOUGHT IT (Hopkins County)

As one person described it, "a forgotten town with an unforgettable name." Who'd Thought It was apparently organized as a farming community sometime after 1900 just north of fellow ghost town Sandhill (or south - I've heard it both ways) on Farm Road 1536. The first store at Who'd Thought It was operated by one Levi Kearny, and at its height during World War II, the small town had two stores and a number of scattered houses, and the local children attended school at Sandhill. In my own search for the town, I have yet to find any remnants of this community with the funny name, and I haven't even found Who'd Thought It on any maps in the archives of Hopkins County. I have apparently found a few scant remnants of Sandhill as well as a map giving its location as just north of Farm Road 1536 east of Tira, but if anyone has some information about the locale and fate of Who'd Thought It, please share.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

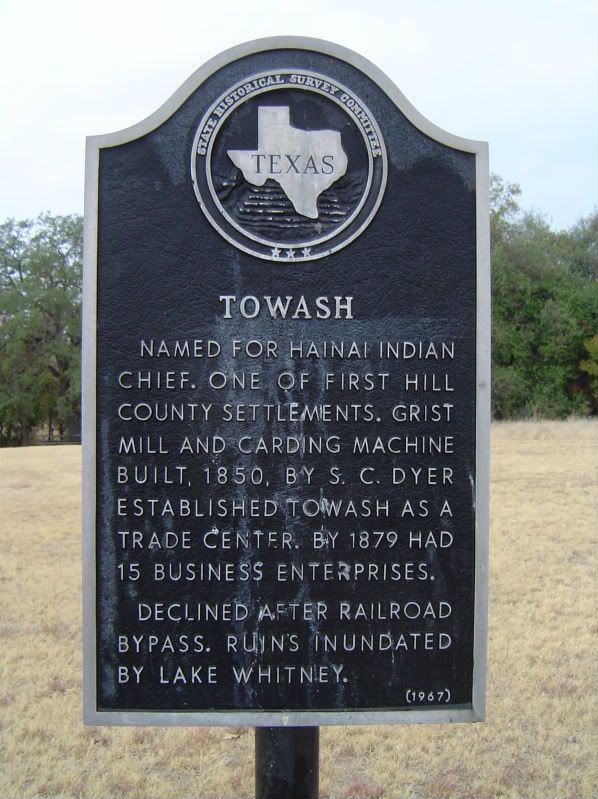

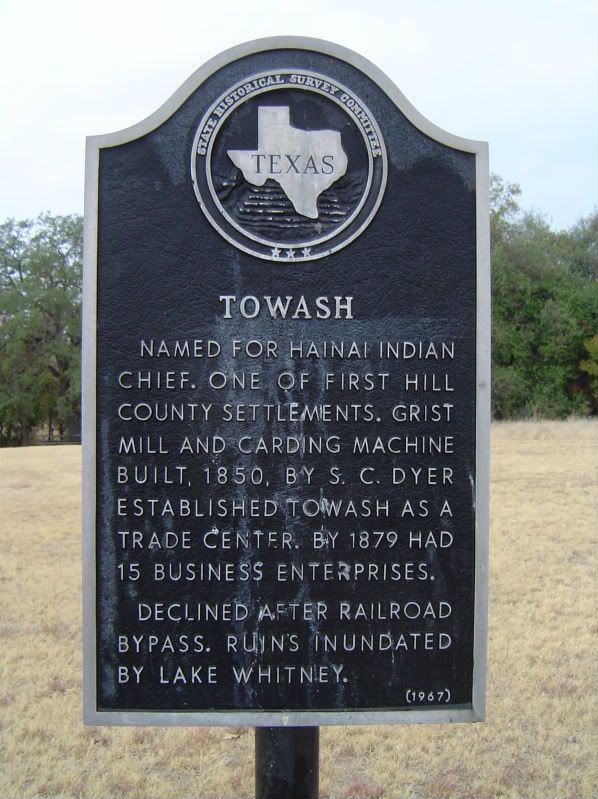

Towash (Hill County) - August 2011 photos

First, a little extra history about outlaw John Wesley Hardin's infamous Christmas gunfight at Towash from the folks at The History Channel's website:

On Christmas Day in 1869, he went to the tiny town of Towash, Texas, seeking some holiday companionship and a good game of cards. Hardin apparently lost his happy holiday spirit when he argued with a man named James Bradley over a card hand. The confrontation escalated, and the men agreed to settle the dispute in a classic street face-off. Though such showdowns--or walkdowns, as they were sometimes called--were far less common than western books and movies suggest, they did occasionally occur, particularly among southern gunmen who continued to embrace the ideal of the gentlemen's duel. Late in the day, the two men faced each other in a deserted Towash street. Bradley shot at Hardin but missed. Hardin killed Bradley with bullets to the head and chest.

As stated earlier on this blog, the site of Towash was permanently inundated by Lake Whitney in 1951, never to surface again for the next 60 years. And now, photos from the lost ghost town of Towash:

Historical Marker for Towash at Lake Whitney State Park, near what is possibly the largest collection of underwater ruins of the town

Towash Baptist Church in nearby Whitney, TX, built partially with materials from the old Towash site and still in use

Tombstone of Simpson Cash Dyer, one of the town fathers of Towash, responsible for the town's gristmill and wool-carding machine; stone and grave relocated to Whitney, TX

Wooden foundations of a small house or shack in Towash, recently emerging from Lake Whitney as a result of the 2011 drought

Remains of a long-submerged road through Towash, uncovered by the 2011 drought

Enigmatic stone block sunk into the sandy soil at Towash, uncovered by the 2011 drought

An utterly alien landscape of stumps of dead trees at the Towash site, uncovered by the 2011 drought

Will these be the only secrets of Towash that Lake Whitney yields? Possibly, but the current elevation of Lake Whitney as of 6:15pm Sunday evening (local time) is only 317.44 feet above sea level - it's supposed to be about 16 feet higher than that. As it is, however, the folks living at the lake are having to battle some fierce wildfires, and I'm in no mood to brave either the flames or more quicksand, so unless water levels drop even further, this may be all I can discover. But I could be wrong.

In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed these photos as much as I had rediscovering at least a few small pieces of the underwater ghost town of Towash!

On Christmas Day in 1869, he went to the tiny town of Towash, Texas, seeking some holiday companionship and a good game of cards. Hardin apparently lost his happy holiday spirit when he argued with a man named James Bradley over a card hand. The confrontation escalated, and the men agreed to settle the dispute in a classic street face-off. Though such showdowns--or walkdowns, as they were sometimes called--were far less common than western books and movies suggest, they did occasionally occur, particularly among southern gunmen who continued to embrace the ideal of the gentlemen's duel. Late in the day, the two men faced each other in a deserted Towash street. Bradley shot at Hardin but missed. Hardin killed Bradley with bullets to the head and chest.

As stated earlier on this blog, the site of Towash was permanently inundated by Lake Whitney in 1951, never to surface again for the next 60 years. And now, photos from the lost ghost town of Towash:

Historical Marker for Towash at Lake Whitney State Park, near what is possibly the largest collection of underwater ruins of the town

Towash Baptist Church in nearby Whitney, TX, built partially with materials from the old Towash site and still in use

Tombstone of Simpson Cash Dyer, one of the town fathers of Towash, responsible for the town's gristmill and wool-carding machine; stone and grave relocated to Whitney, TX

Wooden foundations of a small house or shack in Towash, recently emerging from Lake Whitney as a result of the 2011 drought

Remains of a long-submerged road through Towash, uncovered by the 2011 drought

Enigmatic stone block sunk into the sandy soil at Towash, uncovered by the 2011 drought

An utterly alien landscape of stumps of dead trees at the Towash site, uncovered by the 2011 drought

Will these be the only secrets of Towash that Lake Whitney yields? Possibly, but the current elevation of Lake Whitney as of 6:15pm Sunday evening (local time) is only 317.44 feet above sea level - it's supposed to be about 16 feet higher than that. As it is, however, the folks living at the lake are having to battle some fierce wildfires, and I'm in no mood to brave either the flames or more quicksand, so unless water levels drop even further, this may be all I can discover. But I could be wrong.

In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed these photos as much as I had rediscovering at least a few small pieces of the underwater ghost town of Towash!

Monday, September 5, 2011

Yet another occupational hazard

Quicksand.

While tromping around on the newly-expanded shores of Lake Whitney this weekend in search of more remains of the ghost town of Towash, yours truly stepped on what looked like relatively stable ground in a lakeside mud pit, only to watch his left leg sink up to his knee in quicksand in less than a second.

All is well - I remembered the "what to do" checklist in case of quicksand and freed myself from the liquified soil. Suddenly, I was done with exploring for the day.

I share this with you as a precaution for anyone who wants to go exploring ghost towns. Some of these vanished communities are located in out-of-the-way places that are home to rough terrain, poisonous spiders and snakes, and the occasional pool of quicksand. If you decide to go exploring, be prepared, be well-equipped - and be careful.

PS - Towash site photos coming soon, I promise!

While tromping around on the newly-expanded shores of Lake Whitney this weekend in search of more remains of the ghost town of Towash, yours truly stepped on what looked like relatively stable ground in a lakeside mud pit, only to watch his left leg sink up to his knee in quicksand in less than a second.

All is well - I remembered the "what to do" checklist in case of quicksand and freed myself from the liquified soil. Suddenly, I was done with exploring for the day.

I share this with you as a precaution for anyone who wants to go exploring ghost towns. Some of these vanished communities are located in out-of-the-way places that are home to rough terrain, poisonous spiders and snakes, and the occasional pool of quicksand. If you decide to go exploring, be prepared, be well-equipped - and be careful.

PS - Towash site photos coming soon, I promise!

Thursday, September 1, 2011

State park to open a short drive from Thurber

I just learned a few minutes ago that the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has acquired a 3,300-acre tract for a future state park that will probably be located 6-7 miles away from the Erath County ghost town of Thurber. The land is located closest to the Palo Pinto County town of Strawn and straddles both Palo Pinto County and Stephens County.